Franz Nicolay has been all over the world- as a former member of World/Inferno Friendship Society, The Hold Steady, and Against Me!, he's sailed the seven seas and has braved at least six continents. But recently, he went where few dare tread: Washington, D.C.!

As a supporter of the Music First Coalition, Nicolay lobbied congress to change copyright law so that performers on sound recordings receive royalties during radio play. (As Nicolay points out, the only other major countries to deny performers this right alongside the USA are North Korea, China, and Iran!) Nicolay is a guy that knows what he's talking about so read his compelling explanation on why performers should get a cut of radio income, below.

Copyright law needs to be changed so that performers who appear on sound recordings receive royalties from radio play

Franz Nicolay.

What’s this? I suppose you’d call it an op-ed - there’s a big opportunity coming up whereby American musicians stand to make an extra $100 million a year, and I wanted to let you know about it. I understand that nobody likes to hear musicians talk about money, even when it’s a legit issue (Lars was right!) But there’s a reason why many—most!—of the musicians we like quit doing it at some point, and it’s not (only) because they’re out of ideas, it’s because there are institutional barriers that keep music from being a sustainable career for grown-ass people. And it seems to me that as music fans that should be a concern. And as people who believe in fair play that should be a concern—the issue is not that there isn’t money in the music business. There is. As long as literally everyone in the country listens to some kind of recorded music, there’s money there. The issue is how little of it goes to the people who make it.

In this particular case, the big issues are twofold: performers don’t get paid royalties when their recordings are played on the radio, and recordings made before 1972 aren’t protected under federal copyright law.

What do you care? On May 11 I went to Capitol Hill with a collection of artists, along with the advocacy groups Music First Coalition (http://musicfirstcoalition.org), Future of Music Coalition (futureofmusic.org), and Content Creators Coalition (http://www.c3action.org/), to lobby Congress on behalf of the Fair Play Fair Pay Act (https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/1733/text), which will come to the floor in the next session which starts in January.

Who came? The headliners were Roseanne Cash, T-Bone Burnett, one of the Four Tops, Joe Henry, and Rodney Crowell, but also included the head of the Nashville chapter of the musicians’ union, the co-head of Daptone Records, members of Antibalas, the singers from Cake, Soul Coughing, and Clap Your Hands Say Yeah, one of the guys who wrote “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,†Garth Brooks’ pedal steel player, and a couple dozen others from various walks of musical life.

Buncha oldies and has-beens eh? Well, this is a little bit of the point—the music business runs on a constantly-refilled pool of young, semi-amateur musicians eager to do some touring, put out a record or two, and get some fans, who don’t think too much about it as a career and melt back into regular lives by their late twenties. And in their first flush of success, most musicians don’t spend too much time questioning the institutional structures, from a combination of naivete, not wanting to rock the boat, time and creative pressures, and a natural belief most people hold that they’re the exceptional artist for whom the laws of popular gravity don’t apply. So it is often musicians in their mid-thirties or later who, once the first arc of their career trends down, take a hard look around and realize they’re staring down the barrel of several decades of slogging it out in the trenches, with a decade-long hole in their resume that prevents them from going back to a “real†job, and start asking real questions about the obstacles that keep musicians from a middle-class life.

For what? The Fair Play Fair Pay Act closes some egregious loopholes (http://www.musicfirstcoalition.org/fairplay_for_fairpay) in the ways musicians are compensated for terrestrial broadcast use of their recordings. So once again:

Performers don’t get paid royalties when their recordings are played on the radio.

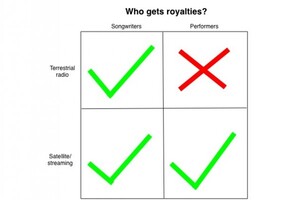

Huh? It’s true. Let’s split broadcast royalties into four quadrants: songwriters, performers, terrestrial radio (AM/FM), and satellite/internet radio (SiriusXM, Spotify, etc). Three of the quadrants get royalties: Songwriters get royalties for play on terrestrial radio and satellite/internet radio, and performers, via SoundExchange, get royalties on satellite/internet radio (only on recordings made after 1972, which is another loophole (https://www.plagiarismtoday.com/2013/08/29/whats-the-deal-with-pre-1972-sound-recordings) this bill aims to fix). But performers don’t get royalties when their recordings are played on terrestrial radio—a $16 billion a year industry built on the backs of popular music recordings.

This affects many different kinds of performers:

- Performers who don’t write their own material. This applies not only to famous cover songs (the Clash’s “I Fought The Law,†Hendrix’s “All Along The Watchtower,†Jeff Buckley’s “Hallelujah,†Joan Jett’s “I Love Rock and Roll,†Johnny Cash’s “Hurtâ€), but to singers who are primarily interpreters, not writers. Think of Aretha Franklin’s “Respect,†Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You,†Frank Sinatra’s “New York, New Yorkâ€: none of them have ever received royalties for radio play. CD/LP sales, yes, but not radio play—a distinction ever more important with the cratering of physical sales.

- Session musicians and hired guns. These are musicians who, while they may have come up with memorable hooks, never received more than their flat work-for-hire pay. Think Hunt Sales’ drums on “Lust For Life,†or Herbie Flowers’ bass on “Walk On The Wild Side,†for which he only ever made his $50 session fee. This also applies to famous house bands like LA’s Wrecking Crew, the Motown house band, or the Muscle Shoals rhythm section, who despite playing on hundreds of famous records, don’t receive royalties.

- The other guys in the band. Most bands have a primary songwriter or songwriters. While some bands decide early in their careers to split songwriting credits equally (R.E.M., Radiohead, and U2 are prominent examples), most don’t, with success, this quickly creates a class system within bands wherein the singer and guitar player, let’s say, suddenly have big royalty checks coming in while the bass player and drummer are still trying to hold down bartending jobs. (So, for example, Danzig gets royalties when “Where Eagles Dare†is played on the radio, but the rest of the Misfits don’t.) This is obviously a huge friction point in the longevity of a band. A royalty system that compensates all the musicians who create the sound on a popular record would go a long way toward alleviating this inequality.

- Older musicians. The standard answer for musicians’ complaints about the state of the industry is “You just have to go on tour more.†(I’ve made that argument myself - http://indigestmag.com/blog/?p=7937) But there are many musicians who, for a variety of reasons, can’t tour. For musicians outside the constrained musicians’ union framework, there is no 401(k), no retirement plan, and many of them have been freelancers whose life income has been outside the purview of Social Security pay-ins. So for aging sidemen without a regular gig, performers (think Motown or doowop vocalists, or country artists) who weren’t songwriters, or any number of musicians whose health or other factors prevent them from touring, a performance royalty would be a valuable lifeline.

- Producers and engineers. This is a bit of a footnote, but producers and engineers have been a major part of how records sound at least since George Martin and Phil Spector, and this bill gives them a slice of royalties for radio broadcast as well.

Oh come on, Beyonce seems like she’s doing fine. There will always be a successful class of stars. There will always be an incoming class of semi-amateurs. But in between, like in so many other lines of work, is a squeezed and disappearing musical middle class. Many of these inequities used to be papered over by CD/LP sales. But the disappearance of that money, which isn’t replaced by miniscule streaming royalties, has people taking a hard look at ways money that should go to musicians is siphoned off. Do we really want to live in a world where music can only be made by corporate pop stars on one hand and amateurs and part-timers willing to work for nothing on the other?

Are royalties for performers a normal thing? Yes. In fact, the United States is the only country besides China, North Korea, and Iran that doesn’t pay performers royalties for broadcast—not the kind of company one usually wants to keep, and one usually associated with policies like mass incarceration and the death penalty.

But it’s more than that. Because the US doesn’t offer a performance royalty, foreign royalty organizations refuse to distribute overseas royalties to American performers because we don’t pay their performers for American airplay. The royalties for “Respect†get collected, but they get spent in the UK instead of going to Aretha, because the US doesn’t pay the Clash for “I Fought The Law†(Otis Redding and Sonny Curtis’ estates, respectively, get paid in both cases.)

So an estimated $100 million a year in royalties that would go to American performers—popular music is, after all, one of our most defining cultural exports—is channeled back into, say, European arts funding. Great for the squats, youth centers, and subsidies that make Europe a super place to tour, but better if it came home.

So—to use a personal example—I can receive performance royalties for playing on Frank Turner’s England Keep My Bones, because it was recorded in the UK and I registered with the UK performance royalty organization PPL—but not any of the more than 100 other records I’ve played on.

Who’s for it? Every presidential administration since Carter. The National Endowment for the Arts. The top copyright official of the government. Pandora and SiriusXM, who suffer competitively from the fact that they pay a royalty and their AM/FM radio competitors don’t. The AFL-CIO and the NAACP, who see the current system as an exploitation of workers and African-American artists, respectively. Many more.

Who’s against it? The National Association of Broadcasters—that is, big radio, ClearChannel and the like, who despite their $16 billion in profits based on selling advertising on music people want to listen to don’t want to break off a piece for the musicians. The bill has carveouts and steep discounts for small broadcasters (public radio, college/community/non-commercial radio, religious stations will all pay between $0 and $500/year) and the National Federation for Community Broadcasters have endorsed it, so it’s only the big corporate radio interests who are resistant. Their claim is that airplay serves as free publicity that translates into album sales. It’s like Netflix saying they have the right to air “The Wire†and only paying residuals to the screenwriters, since it’s free publicity for the actors who can, you know, sell “Bubbles†T-shirts.

So is this thing gonna pass? Well, it failed in 2015, in the face of ferocious lobbying by corporate broadcasters. But the revised bill has important bipartisan support and has made for unusual bedfellows. The Congressional sponsors include representatives with important musical constituencies—Democrats Jerry Nadler (from New York) and John Conyers (Detroit) and Republican Marsha Blackburn (Nashville)—as well as powerful Republican Darrell Issa, who invented the “Protected by Viper†car alarm system and holds several patents, and so is interested in intellectual property and royalty concerns.

My subgroup even sat down with Tea Party eccentric Louie Gohmert (http://www.slate.com/blogs/bad_astronomy/2016/06/01/texas_gop_congressman_louie_gohmert_seems_to_have_a_problem_with_gay_space.html) who, say what you want about his politics, was by far the most entertaining meeting of the day. In between stories about former Texas Congressman Charlie Wilson (of Charlie Wilson’s War fame) and Donald Trump (“I’ve met Mr. Trump a few times. That hair—it’s like when you’re talking to a woman and you can keep your eyes off her chest; I couldn’t stop looking at it. Where does it come from? Where does it go?), said he was at least sympathetic to the bill, since he has a daughter who is an aspiring singer-songwriter in Los Angeles. He played us her video on his phone.

But the message was clear: musicians and people who care about music have to make themselves heard, because the opposition voice is a hugely well-funded industry with massive lobbying firepower.

Why should I care? Because it’s a fundamental issue of fairness. Because it’s rank exploitation of artists by a cartoonishly greedy corporate industry, the one that has eliminated independent radio and instituted robot playlists across the country. Because it affects the most vulnerable elderly musicians. Because it’s one of a number of things that can help rebuild the musical middle class. Because we all know the myriad ways in which musicians get a raw deal, and this is one actually has a chance of getting fixed.

Email your support to your congressional representative here: http://www.musicfirstcoalition.org/take_action

Read more about the Fair Play Fair Pay Act: http://www.musicfirstcoalition.org/fairplay_for_fairpay

http://futureofmusic.org/blog/2015/04/12/look-inside-fair-play-fair-pay-act

http://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/congresss-chance-to-be-fair-to-musicians

Future of Music Coalition’s infographic on how music’s money flows: http://futureofmusic.org/article/article/music-and-how-money-flows and their research on artist revenue streams, that is, where musicians’ incomes really come from: http://money.futureofmusic.org/

Franz Nicolay’s book “The Humorless Ladies of Border Control: Touring the Punk Underground from Belgrade to Ulaanbataar†(http://www.powells.com/book/the-humorless-ladies-of-border-control-9781620971796) comes out Aug. 2 on The New Press.