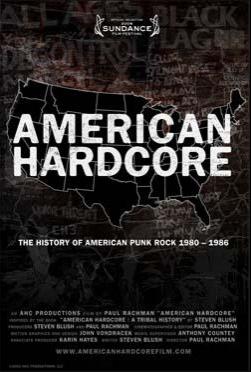

We recently had a chance to speak with Paul Rachman and Steven Blush, the film makers behind the recent documentary, American Hardcore: The History of American Punk Rock (1980-1986). The film was one of the most thorough looks at the rarely examined influence of the second wave of Punk Rock, particularly the vast influence of bands like the Bad Brains, Minor Threat and Black Flag.

Spiritually adapted from Steven Blush's controversial book, of the same name, the film speaks with all the notable figures from that period, including Greg Ginn, Ian MacKaye, Keith Morris and many, many others. The film presents a window into that world, eschewing narration or any exposition to present the original stories from the original people involved.

So how does it feel to have the film out there now?

We all survived this really fucked up time where no one got their due, no one got paid, no one got laid, no one got anything out of it.

Well itâs good, you know, this is a long process. Steven and I ended up making the film very much like this music was made. Iâd taken the book around to a few companies early on to see if anyone wanted to give us money to make it, and you can imagine the reaction from looking at the cover of Stevenâs book of a bloody face, you know it didnât quite click. In hindsight that was the best thing for this film because it allowed us to make it the way this music was made. The film has a little bit of that feeling.

One thing that really stuck out to me is that people have made so many documentaries about punk, especially rooted in England, but everyone glosses over this period in the 80s when America really developed its own identity.

Paul Rachman: That was important to us, that was the road we took. Weâre going to tell the story that has not been told; weâre going to validate the lives of all these people who were not only our friends, but were people who meant a lot to who we became.

Paul Rachman: This is the greatest music story never told. It was just so important, this music was so important to us, and these bands were such heroes to us, and they had never gotten their due, it was beyond time that this happened. These bands werenât just cool bands, they were really influential. You wouldnât have the music today if it werenât for these bands. From the obvious stuff like stage diving and slam dancing and tough lead singers, but also to the more important things like DIY records, independent touring networks.

Thatâs all the legacy of Black Flag, Bad Brains and Minor Threat, and bands never really got their due for that.

You also gave a lot of credit to HR and the Bad Brains.

Paul Rachman: Yeah, I was lucky enough to work with those guys a lot when I was younger, and I started shooting them a lot. I became a filmmaker because of hardcore, I wasnât close to it Boston, I was in college there in 78-82 and when I saw the Bad Brains it just brought it up to another level. And HRâs interview was great because I got him on a good day and he remembered these things that he really helped to establish in DC in the very early 80s, late 70s. You know, that whole way of finding alternative spaces to do shows and making sure that the band and the audience can meet after a show. All those things were things that HR really had a lot to do with.

Paul Rachman: The Bad Brains are also really fascinating because they are the best and the worst rolled into one. They really are this incredible band and this incredible positive message, and then all this incredibly negative baggage. But thatâs what great artists are; great artists are flawed. You know what Iâm saying?

Definitely.

Paul Rachman: Great artists usually never get their due, because theyâre not savvy at first, they donât know how to market themselves. So, what happened to a lot of these guys is that they either didnât know how, or they werenât thinking about commercial pursuits. And they were kind of fucked because of it because kids came up along later and took a similar sounding style, and they knew how to market themselves. But the Bad Brains were - if Ian Mackaye speaks in such reverent tones of the Bad Brains, and if thatâs how he got to where he is, then that must be damn important.

Theyâre one of those bands that you always have to separate their music from some of the strange things theyâve sad. Every time Iâve ever written about them, Iâve always been forced to say "despite some of HRâs statements" the Bad Brains are still great.

Paul Rachman: They were the one band who you could really separate their personal story from their musical legacy.

Paul Rachman: They were repeatedly forgiven over and over again because the music was so great. They would show up four and a half hours late for a show, you know, it was unheard of! It wasnât half an hour late, it was half a day late! These things are unforgivable in a way, but they were forgiven because they were just so incredible.

On the subject of the film, what kind of response have you been getting so far?

Paul Rachman: Well its been good, I think that on one hand we had a couple of premieres, one in New York and one in LA, and a lot of people who were in the movie came to those. They really loved it, some of them thanked us, a lot of them feel validated. Theyâve been ignored for so long, other than within their own subculture, that it felt good, they were really proud to be a part of it. Steven and I were participants in this when we were kids. We werenât in bands but we were part of the scene, we were participants and this is our way of - Steven and I came along and we had the tools to tell the story in an authentic manner and I think we accomplished that.

I canât stress enough how important it was to see that, because this is something that is always glossed over in history because the British scene obviously had so much attention with the Sex Pistols and all the antics and stuff, and the Clash were obviously amazing but the American scene kind of defined a lot of the ethic, not even just the music. I donât think Fugazi sounds anything like the Clash or the Sex Pistols but they're definitely the spiritual heirs of a band like the Clash.

Paul Rachman: Thatâs one of the main points in this film that - yeah there were some awesome songs there were plenty of awesome songs, but its really about the ethic. Its really about the do it yourself, disdain for authority, donât do things just for the money, be fearless in your pursuit, thatâs what hardcore was.

Paul Rachman: None of these kids, when these bands started, none of these kids were worried about failure, there was no place to fail to. None of these kids cared what other people thought of them. While some of their peers in high school, some of their daily lives were all about what people thought of them. These were kids who were taking this way of life, they were coming into manhood and taking these very radical, ethical ways of living their life, very strong willed, on solid ground attitudes. And it worked.

Paul Rachman: With this film obviously weâve got lots of good mainstream reviews, but the proof is in the pudding of the really wonderful reaction weâve got from the participants. Scott from the Bad Brains kissed Paul.

Paul Rachman: Scott came up to me and kissed me on the cheek and said "You did it right." Thatâs all he said to me. Then we talked about other stuff.

Paul Rachman: We got that reaction from everyone, and that says it all, you know what Iâm saying, we had tremendous ones on us to get this right. All these bands put their legacy in our hands and we did not take it lightly. You know, weâve got nothing but love back so far, so that says a lot.

One thing that really stuck out to me is that you guys really had unfettered access to a lot of people who never show their faces. Like Greg Ginn who has been almost invisible since Black Flag split up.

Paul Rachman: We didnât come in as like interviews with a list of questions that were going to lead us down this predetermined script. These were conversations we had that were intimate and honest. The process for this film was really weeding out or carving out this story out of these peopleâs conversations with us. We didnât have this preset pattern, or we didnât rewrite questions according to what other people had said. We really wanted this pure honesty from everyone, and I think we got that.

Paul Rachman: You raised a really good point, most of these people are not available to press. They would hang up on press, half of these people. They trusted us, and that comes back to only one thing - that we werenât - neither of us are saying that we are major players in the original hardcore scene, but we were participants and Iâd say about 20% of these people crashed on my floor back in the day. So it was a very fraternal experience, and I donât mean frat boy, I mean like war veterans.

We all survived this really fucked up time where no one got their due, no one got paid, no one got laid, no one got anything out of it. What we did get is this intense community with this. I think a lot of - for myself, starting with the book, it was just about finally documenting it. It had nothing to do with - one thing, one major moment in my decision to work on the book was the History of Rock and Roll series on TV. It was very good but like youâre saying it goes straight from The Clash to Nirvana like nothing else ever happened.

People would come up to me and talk to me about hardcore and theyâd always have it wrong. People have been pulled with legend and lore and it would get skewed as time went one because there were no Black Flag articles in Rolling Stone magazine, and if it was it was to make fun of it. There was no MTV videos, there was no real documentation. There still is the manifestation of that effort to kind of finally, finally tell the story right.

Paul Rachman: This film has everybody in it, you have - the participants are all there, you have other films, like - oh thereâs some films that talk about Black Flag, and thatâs all they talk about! So it was really about telling the story of this complete scene as an entity during this time period.

The book itself has always provoked a lot of heated discussion; itâs always been kind of controversial, but have you had that kind of controversy with the film?

Paul Rachman: Well I think that when we set out to make the film, I didnât want to make a film that - documentary has changed a lot, especially in the last five-six years, and I really saw this as a more traditional documentary, back to the days of the Maysles brothers where you really let your subject tell their story, however long that might take. You might have to shoot several hundreds of hours of footage to get that story told properly, but that was the process.

I really wanted to make a film that was this first-person account from the people and just let their story be told. I didnât want to have narrators or expert opinions or people disagreeing with this and that, and it not be coming from the people who wrote the music. I think that on the one hand, that makes the film very intimate on one hand, and it does kind of work at avoiding some of that controversy. But that controversy - you dwell on one or two little things that happened over a six-year period, however big they are, but itâs not what the movement was about.

Paul Rachman: Thereâs no narrator to the film, thereâs heavy narration by people in the book. But I felt that was necessary because I actually experienced these things. I donât get a lot of bad feedback but most of those people werenât there. Or if the people were there, they donât like if I said that their legacy wasnât as great as they thought. Thatâs truth, Iâll swear on bibles over that stuff.

Paul Rachman: But you know a book and a film are two very different things. You can have a 3-400 page book, you can use quotes of people at the end of the book and at the beginning of the book. You can edit sentences. Film canât really be built that way. Film needs to have this flow, and this energy that keeps on moving forward to keep your interest, keep you in your seats. A book you can put down and pick up an hour later or a day later, itâs a very different thing. So inherently we wanted to make a film that really stood up as a solid, intense, hundred minutes in a movie theatre.

I guess the road map for punk documentaries kind of was set by Don Letts and stuff, Iâm just wondering if that had any influence on you either as a "letâs do this" or "letâs not do this" kind of thing?

Paul Rachman: No, not at all. We locked ourselves in a basement. Just as a filmmaker, personally, Iâve always had this - even if you just look at my music video career, all of my videos were very different. I really never got bogged down in what other people were doing, and that also, its good in one sense, but it hurt me in a sense that in terms of being commercially viable, people always kind of want to know what theyâre buying, less hirable or more of a risk. But with this film it was really about the subjects, they really drove the style of the film.

The Decline of Western Civilization is a really great movie, it kind of is one of the important films talking about the American scene, but it presents it in its nascent years, Greg Ginn in the DVD, youâll see t Greg Ginn talking about the day they went to that shoot for the Decline, and Decline came out in 1981 so it was probably shot in 80 and 79, and Black Flag was nascent, that was new, and Greg Ginn goes "yeah we went to Hollywood to do this movie Decline, and we had an audience that never looked like any audience we had ever had before."

So American hardcore really has this 25 year perspective on this particular brand, this particular movement, and type of music. And thatâs what keeps it unique. Don Letts was great with the English stuff, he doesnât really know that much about the American stuff.

One question that is always raised about a documentary is that it tends to bookend an event, as if to imply that hardcore isnât still happening.

Paul Rachman: Well there was an ending - the people in the movie talk about how it ended for them, things change. But I think the most important thing is that the environment is different. I think Greg Ginn once again describes it perfectly, Ian Mackaye and Greg Ginn have two great quote about their endings.

Greg Ginn talks about 1986 he ends Black Flag because the environment that surrounds the music, the scene and the band - is different. It is no longer the same. So the band cannot keep going on being the same band anymore.

Ian Mackaye gets sick of the violence. The scene becomes too violent and heâs at a Minutemen show and he punches somebody for the last time. Everything changes, so I think the environment that existed between 80 and 84 was very different - you had this time and space where you had this intense new music, these energetic kids with an avid, invested audience.

The audience participated, helped make things happen, propelled it from town to town. Thatâs how it became a movement, because it had this avid, intense audience that was willing to propel it. Its not like you could find this stuff in stores or anything like that. You couldnât call your friend in the next town and say "go to the store and buy this". It wasnât that easy. You really had to help make the show happen. And then you had Ronald Reagan coming in and trying to turn the clock back to 1950s America. So you had all these things happening which all kind of connected in a weird way to propel this into a movement.

The American Hardcore film is a tribute to the original hardcore bands cause theyâre our heroes. These guys deserve to speak without Sean Penn narrating

I think today as in any day you always have great art, you have intense music, you still have hardcore, but the environment is completely different, its not the same thing. Kids are less bored - kids in the suburbs are less bored, theyâre on their computers and iPods and all that. Not that thatâs a bad thing, but itâs just different. So it canât be the same movement that it was, but there will probably be something new in a few years that will tear the walls down again.

One thing that definitely seems interesting to me is that lately weâve been starting to see more documentaries about this era. The thing about documentaries is that they kind of lend this air of finality to something.

Paul Rachman: You want a beginning, a middle and an end (laughs). I guess in a way I think that in our case, the people we talked to had their ending to it. Our film is very specific, 80 to 86. We really wanted to keep it narrow, we wanted to keep it specific; we wanted to keep it about something that we knew best, that we could make from our gut, from our instincts. Thatâs what we chose to do. I think that with documentaries actually becoming more - documentaries are starting to become more about the people who are making them, like Michael Moore and all this, and itâs about him its not about the subject.

I think thatâs whatâs really changing in the documentary world, some subjects thatâs great for and some not. In this one we really chose to take a more traditional route.

You definitely donât see much interference from the film makers. Michael Moore definitely is writing an essay in a documentary form rather than actually providing a "document" of anything.

Paul Rachman: And that was - we set out to do that from the very beginning. It was an important factor in the making of this film.

Paul Rachman: Yeah this was about letting the guys be heroes through the five years of hardcore speak unfettered. The American Hardcore film is a tribute to the original hardcore bands cause theyâre our heroes. These guys deserve to speak without Sean Penn narrating. When we say thereâs an air of finality about a punk rock story, weâre not saying that thereâs not kick ass bands today, weâre not like these old guys like "there hasnât been a good record in ten years." We donât feel that way.

Previous Story

Contests: William TellNext Story

Contests: New Tim Armstrong tracks to be released each Tuesday, first available nowGreg Ginn's Black Flag announces full USA 'First Four Years' tour

e.town concrete, Cold as Life, Black Flag headline TIHC 2024

Keith Morris says OFF! to go on hiatus after movie premiere, Circle Jerks to record new album

Black Flag to go on 'First Four Years' tour

Original Misfits, Social Distortion, Iggy Pop, Fishbone, Scowl, more to play No Values

Descendents, Vandals, Adolescents more to play Punk In The Park 2024

Black Flag announce new leg of My War Tour

Rodney Bingenheimer accused of sexually assaulting six teenage girls

Minor Threat to release 'Out of Step' Out takes

Israel Joseph I (ex-Bad Brains) releases solo album