Matt Miner is passionate about animal rights activism, and has been involved with the animal rights movement for over a decade, but he also has a passion for writing comics, studying the craft under Scott Snyder (Batman, American Vampire). With Liberator, from Black Mask Studios, Miner, in collaboration with artist Javier Sanchez Aranda, is combining these two passions, looking to tell a compelling story while also bringing a topic he's passionate about to a new audience.

Matt is also a contributor to Black Mask's Occupy Comics project, having been assisted by Occupy Sandy volunteers in the aftermath of the hurricane.

News Editor Andy Waterfield recently spoke to Matt to find out more about Liberator, the politics around it, and how he and his wife incorporate their beliefs into their lives.

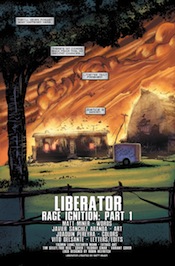

First off, could you introduce the book, and the main concept behind Liberator? Liberator is a four-issue miniseries being published by Black Mask Studios. Black Mask was founded by Steve Niles, who wrote 30 Days of Night, and a bunch of other horror comics. He was also in the DC punk band Gray Matter. It was also founded by Matt Pizzolo; who wrote Godkiller; and Brett Gurewitz; of Bad Religion and Epitaph Records.

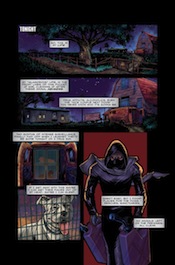

The concept of the book is a gritty, underground, animal liberation, adventure / vengeance story, with two young antiheroes who take direct action in defense of animals. So, instead of fighting intergalactic war, or taking out supervillains in tights, theyâre more grounded in reality, and based on real people who actually do this kind of thing in real life.

Youâve previously described Liberator as âa vigilante vengeance story with underground, hardline, animal activists.â How does vengeance, as a concept and in practise, sit alongside characters whose politics are, presumably, rooted in compassion?

How do you mean, exactly? How is someone vengeful without being violent?

Yeah, I guess.

Okay, well, that depends on your definition of violence. To me, you canât be violent to a trash can, a pane of glass, an empty building, or an automobile thatâs unoccupied.

These people, while theyâre taking action in the night to save animals, theyâll also destroy the property of these abusers to make it less comfortable to continue on with their abuse of animals. It also makes it less profitable to continue abusing animals.

The idea is that, if you put the pressure on, theyâll change their ways, and stop their current course of action, which is hurting animals. In real life, this actually works a lot of times.

I think where I got the idea that there was violence against the people abusing animals was the blurb comparing the book to The Punisher on one level.

Right, Itâs definitely in that vein. If you ever read The Punisher: War Journal of the â80s, where you have Frank Castleâs brooding internal monologue as heâs carrying out his actions; itâs kind of that same feel. Our heroes donât actually hurt anyone, but they will fuck up someoneâs life.

You have covers on the book by Tim Seeley, but whoâs doing the interior art?

The interior art is Javier Sanchez Aranda. Heâs an artist out of Spain; heâs done work on stuff like Dungeons and Dragons and he did a series of Star Trek: The Next Generation books.

When I was introduced to him, he really seemed to take to the idea of these underground, direct action, superheroes, for lack of a better term. Heâs really been kicking ass on the book.

Youâre writing from a position of experience within the animal rights movement yourself, in particular as a dog rescuer. Could you explain to our readers what that entails, and what brought you to it?

Iâve been involved in the animal rights movement for maybe ten years, in different aspects. I started off pretty heavy with the SHAC campaign, which is âStop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty.â Theyâre the people outside of homes and offices with bullhorns and signs, trying to shut down the Huntingdon Life Sciences lab. Iâve worked on anti-fur campaigns; Iâve worked on vegan outreach stuff… a lot of different aspects.

We recently moved out to the Rockaways in New York. Out here, itâs very low income, thereâs a lot of crime, and thereâs a lot of dog fighting, and thereâs a lot of companion animals, dogs and cats that are in need of rescue. We decided our time is better spent actually going and physically helping animals than protesting outside of someoneâs house.

Presumably a lot of this stuff is illegal at some level, or on the fringes of legality. How do you navigate that sort of activity, where you are at risk of people either responding with violence themselves, or involving law enforcement?

I think itâs important to point out that my wife and I, when weâre doing dog rescue, we donât do anything illegal.

Weâre big supporters of the underground, and I have friends in jail that Iâve made since theyâve been arrested. I have friends in jail that I waved goodbye to as they were being taken away that I didnât know were involved in illegal activities, but we donât do anything illegal, even though we do support the tactics of the underground movement.

What my wife and I do… weâre helping strays, ferals, weâre getting dogs off of chains with embedded collars… Weâre doing things like that. Where our heroes are more representative of the underground movement, my wife and I are more just your above ground dog rescuers.

That makes sense. I was wondering.

Yeah, we donât do anything illegal, but yâknow, Iâm a big supporter. If somebody has the passion in their heart to take action in the night, I think thatâs awesome. Thereâs so many animals out here that need help without having to do anything illegal, why would we?

Because Iâve got friends who got caught up in this, because Iâve been a supporter of the underground for so many years, Iâm writing from a place of authority on the matter, but not experience.

As a writer, when youâre approaching something about which youâve got such clear moral conviction, do you find it difficult to navigate that conviction while also getting into the heads of characters who arenât necessarily in line with that conviction themselves?

Not really. In terms of writing from a place where the character may not agree with the views of the book, thatâs not a problem. Iâve always been able to put myself in the shoes of others, and see other peopleâs motivations; the reasons why they do things; even if I donât agree with them. Thereâs no issue there.

I think something that is similar, that a lot of people have brought up to me, is theyâre concerned that the book is going to be preachy, or itâs gonna be a diatribe about animal rights, which itâs not. First and foremost, itâs an awesome, kick-ass story with eye-popping art. Itâs just told within this world of underground, hardline animal activism. Itâs about our characters, and their story, but itâs told within this world.

Itâs weird, because no-one ever levels that criticism against Batman, when you could argue, "Isnât Batman just a diatribe about gun crime?" Which to some degree it is, but thereâs other stuff beyond that.

Yeah, and nobody ever freaks out about Batman or Spider-man being violent either; because they donât kill people, itâs âokay.â Whereas, I have accusations leveled at me that Iâm promoting arson, property destruction -

Even before the book has come out?

Yeah, just from the art. People see the fire, theyâre like, "Oh, youâre promoting arson!"

Iâm like, "Iâm not promoting anything! Itâs a comic book! Spider-man throws people through windows, and Batman breaks bones to get information, but youâre not upset about that, youâre upset about the guy whoâs burning an empty barn!"

Itâs all pretty ridiculous. Itâs a comic book. Comic books come from places of extremes, and this oneâs no different in that respect.

How has the reception been (other than that) more broadly amongst comics readers so far?

The receptionâs actually been extremely positive. When I first started shopping the book around, and I started showing it to my professional friends, they were pretty impressed with how ballsy the book is. The overall feedback has been pretty positive.

Youâve got a cover blurb from Scott Snyder as well.

Yeah, he was actually my teacher. I took a class from him, he helped hone my craft, and helped me craft Liberator, and turn it into something better than it was.

In terms of political comics, have you got any favourites from the more established works that have come before?

Sure. I grew up with V For Vendetta, for instance. Who doesnât love V For Vendetta? Thatâs one of my favourites.

We3 by Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely… That book showed me that the concept of vengeance for abused animals could actually work in the mainstream market, so I owe a lot to that book as well.

Youâve also said that the main characters in Liberator, like you, have a background in punk and hardcore. What was your experience of punk growing up, and in what ways do your experiences align and contrast with those of your characters?

Growing up, I was bullied, I was a nerd, I was unpopular. In the late â80s and early â90s, I discovered punk rock; music made by all these other kids who were bullied and were nerds.

I started off with stuff like the Ramones and the Descendents, and moved onto political punk, like Subhumans, Conflict, Crass, Chumbawamba. I found there was this awesome outlet for my frustrations, for my angst, anxiety… There was this outlet to be had in a circle pit at a show. Youâre surrounded by people who understand you better, yâknow? Itâs like a community growing up.

My characters come from that same world, where theyâre influenced by the political messages of the music they listen to, and theyâre part of this punk rock world as well.

The literature Iâve read so far doesnât introduce the characters by name at all. Is that a deliberate decision?

Itâs not deliberate, but I want people to understand that these people could be anyone. Our characters are Damon Guerrero and Jeanette Francis. Theyâre kind of the outcast kids, who take up this nighttime vigilante activism.

Itâs important for people to remember that you donât have to have superpowers or wear a cape or tights in order to be a hero.

As characters, what sort of background have they got? What sort of age are we looking at?

Early 20s. Damon is about 25, and Jeanette is 23. Jeanetteâs a college student, who had a major in biology until she saw what was going on in her schoolâs laboratories. Damon is kind of a slacker/barista type, plays up this loner image so people leave him alone so he can take care of business at night.

Have you got any other creative projects on the go?

I have a story in Occupy Comics, which is also being put out by Black Mask, and all the money raised from that is going back into Occupy-related ventures.

The story is basically about my experiences during Hurricane Sandy, when our house was flooded and how Occupy Sandy was there for us during that time. Thatâll be coming out in July, in Occupy Comics #3.

I have another piece coming out in an anti-bullying anthology, and I have another creator-owned book, that Iâm putting together right now that I canât talk about yet.

I think Matt Pizzolo mentioned the Occupy response to Sandy being faster than a lot of the traditional emergency response groups. I guess he was talking about your experience?

Yeah, he was following me on Twitter. I didnât have phone service really, but every once in a while I could get tweets out. Once the phones came back, and I had reliable 4G access, I saw Iâd gotten hundreds of people following my tweets about Sandy, because every once in a while Iâd be able to get a picture out, and I live-tweeted the storm itself.

Occupy Sandy was here the day after the storm. They were here the next morning. We got hit at night, and in the morning Occupy Sandy was here. It wasnât until three or four days, maybe, that Red Cross was here.

It was a tough time, but the Occupy kids were here immediately. They really, really helped us out here.

Were they based nearby to begin with?

No. Rockaway is a little peninsula down at the bottom of Queens. If youâre thinking about Occupy Wall Street, thatâs at the base of Manhattan; itâs quite a ways away. They came out here specifically for us. They werenât just already in the neighbourhood.

Thatâs incredible. Just logistically, getting everything together, and getting out there, in just a couple of hours. Thatâs really impressive.

Yeah, really amazing. I strongly believe that we, as a community in Rockaway, owe Occupy Sandy a huge debt of gratitude.

Going back to the comic for a second, a proportion of the profits are going to animal rescue organisations. Could you talk about that for a moment?

My wife and I do a lot pit bull and other dog and cat rescue here in the Rockaways, and most of that work is funded straight out of our own pockets. We donât have public funding, and we donât do fundraisers. Unless thereâs a specific animal that needs an operation, we never ask for money from anyone.

My entire portion of the money that comes back from Liberator will go back into our animal rescue work here. I didnât think it was right to do a story about animals without having at least my portion of the money go back to the animals.

I want to be very clear about that. That was one of the goals of Liberator. The first was to bring new people to comics, because Iâve been a comic nerd my whole life, and I love comics. I also wanted to bring animal issues to new eyes, and I wanted to help fund our animal rescue work here.

Thatâs some dedication, putting that level of work in, without any possibility of financial reimbursement down the road.

Youâre reimbursed by the animals that you help.

One of our fosters right now was tied up and abandoned not far from here. She was extremely injured and beat up, and watching her come around, and heal…

Thatâs what makes it worth it.

Liberator is available from the Black Mask Studios online store, or you can pre-order issues from your local comic shop.