Punknews is mega-mega-mega excited for today's stream. Today, we're doing something that we've never done before. Today, we are streaming an unreleased, unissued, unknown album recorded by the Flames in 1980. This is literally the first time the public has ever heard this long lost gem. (And really, this is a long lost gem!)

This record blends jumpy power-pop with the snappiness of early new wave with the edgy lyrics of first wave punk. Just look at some of these titles: "Stabbed to Death," "Contaminated," "Menage a Trois."

If you've been following the Punknews podcast, you'll know that the reason we came across this record was that editor John G found a copy in the bargain bin in a used record store. There was absolutely no record of this album anywhere on the internet. If you are a punk connoisseur, you know how rare that is in this age of mass documentation.

BUT, on the back of the record was a phone number (no area code) written in magic marker. Above it was the name "Michael J. Richards," the guy credited as vocalist and guitarist on the album. The result was a literal one-in-a-million shot in tracking down Richards. The story of this record's re-discovery is nearly as fascinating as the record itself. (And it's a fascinating record, mind you!)

So, for the first time in the existence of man, you, the public can hear the entirety of 1980's The Flames right here. Meanwhile, you can click read more for an extensive history of how this record came (not) to be by John Gentile.

You Have Never Heard of this Band

I can pretty much guarantee that you’ve never even heard of, never-the-less actually heard, Vancouver's the Flames. The band recorded a slick, killer self-titled record in 1980 that hid bizarre and even scary concepts behind a conventional pop format. Their song “You Always Survive” was a tale about getting beat up by the police set to a white-reggae beat. “Do You Love It” was a hard-driving power-pop tune as catchy as anything else released in time frame between first wave punk and the new wave explosion. “Stabbed to Death” is self-explanatory.

But, despite having snappy-as-hell tunes and hard-edged lyrics, there are probably less than 30 people on Earth today that remember this band. Why is that? Well, first of all, they only ever played about two or three concerts. Second, despite self-financing and recording an entire album, it was never released. Indeed, it seemed that The Flames, a long lost gem by any definition, was lost to the ages. That is, until a chance encounter at a record store in Wilmington, Delaware”¦

The Unearthing of a Gem

There’s a record store called Jupiter Records about 25 minutes from my house. Although it’s technically in Wilmington, the store is actually located at a crossroads in the middle of a heavily wooded suburb. The only way to find Jupiter Records is if you go looking for it.

Despite being fairly remote compared to its city contemporaries, Jupiter Records gets a healthy share of used stock in each day, with titles ranging from rock to punk to pop to jazz to weirdo records.

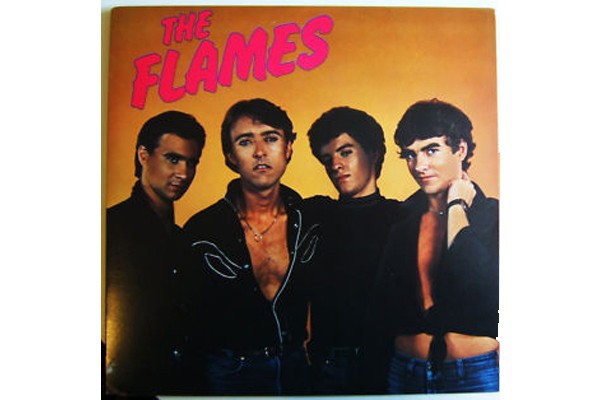

During one of my weekly visits, I was flipping through the new arrival section and came across a record by a band called The Flames. It wasn’t the James Brown band nor was it the Alton Ellis group. Instead, on the cover, four guys in black stared back at me, looking something like a cross between the Ramones and Cheap Trick. I flipped the record over and saw far-out song titles like “Living in Bondage," “Contaminated” and “Punish Me.” The singer was a guy called Michael J. Richards. Was this a punk record? Was it power-pop? Was it disco? The price? Five bucks. I had to risk it.

Without any further info, I took the record home and gave it a spin. I was immediately floored by the album’s pastiche of sounds. It wasn’t “punk” per se, but it had nasty, nihilistic lyrics about suicide, killing other people and a fair share of BDSM references. It wasn’t power-pop, but it has the driving, energized beat of The Jam. It wasn’t new wave, though it had the snappy, clean lines of bands like Blondie and Devo. Rather, it was it’s own thing -- A record created in the miasma of 1980 New York that didn’t subscribe to the rules of any one set genre. In another manner of speaking, it was one of the few truly “rock and roll” records.

While I listened to the record, I tried to dig up information on it via Google, Discogs, Wikipedia, eBay and pretty much any other source you can imagine. But, with a band named “The Flames” and a singer named “Michael Richards,” the band and album was pretty much washed from “˜net existence. There appeared to be no trace of this unique record anywhere.

But then, as I studied the record jacket, I saw that on the back, the name “Michael J. Richards” was written in magic marker with a phone number immediately after it. There was no area code.

Could this be the number of the album’s lead singer? I had to at least try to learn about this album.

Using Google, I figured out that NYC has three main area codes. I picked the longest lasting one. Then, as some of you may recall, we called the number with the guessed area code live on the Punknews podcast. We got an answering machine that sounded like it was the number to a marriage counselor or something like that. Defeated, I left my e-mail address and assumed that was that”

A One-in-A-Million Chance

But then, about six weeks later, long after I had forgotten about this exploit, I received an e-mail from someone named Deanne. I don’t know anyone named Deanne. I opened it up and found the following message:

Dear John

I heard that you want to contact me. I do not have an e-mail address but you may contact me at [this e-mail address].

Sincerely,

Michael J. Richards.

I was thrilled! Could this be the elusive character smirking at me on the album cover? I immediately e-mailed him back, telling him that I found his record and thought it was great.

Michael responded back and stated that he was “blown away” that someone had found his record after 34 years and that he was definitely up for an interview. I then learned that there was a reason that the world was devoid of any information about NYC’s Flames or their sole album -- it was never actually released. The copy in my hands was an exceedingly rare promo copy and after traveling through collections and basements and attics and shops for three decades, the record had landed in my hands. Michael then told me the story of The Flames and his own musical development.

The Story of the Flames

Richards was born in England and when he was eight, his family moved to Canada. After learning to play an instrument, he formed a band called The Royal Family in 1965. The group had some regional success and had two singles that charted, including the “Sometimes/Solitude" single. "Solitude" was a post-British Invasion rocker that mixed together blues influences via the high charged Rolling Stones Abcko singles. (In fact, “Solitude” gained a small reputation as a proto-punk classic when it was included on the Nightmares from the Underworld Vol 2 proto-punk comp released in the '80s.

Following that, the Royal Family slowly disintegrated, but they reformed as Troyka, minus one member from the Royal Family. Troyka, though, was dramatically different from The Royal Family. Whereas The Royal Family kicked out '60s R&B bangers, Troyka bore the marks of the growing prog scene, experimenting with lush arrangements, simple folk strumming and high-concept lyrics.

Troyka’s self-titled LP was released in 1970. And, like The Royal Family before it, became a sort of cult-classic record. In fact, serendipitously, Real Gone Music just re-released the Troyka album in 2014, with remastered sound and bonus tracks.

Soon after that, Troyka disbanded and Richards recorded a new album with one of the members of Troyka in the mid-'70s. After that project, he began to write a series of short, energetic, hard-edged numbers. He decided that he wanted to put together a band to get the tunes recorded.

“Around 1979, I started writing these songs, and by February of 1980, I decided I needed to get something going,” Richards says. “I really wanted to make a move.” At the time, Richards was living in Vancouver, British Columbia and looked in the paper. He saw that a bass player and a drummer were looking to form a band. “Ironically, they wanted to do a keyboard-based new wave band,” Richard says. “I had written these songs on acoustic guitar, but I figured, “˜eh, I’ll give it a try.’ So, I went over there and played the song “˜Contaminated’ on my acoustic guitar and they really liked it.”

The band, then consisting of Richards on vocals and guitar, Pat Post on Bass and Walter Makaroff on drums, immediately started rehearsing. Richards’ plan was to rehearse the album, record it and then shop a finished project to a label. After a short while, Richards’ former Troyka bandmate, Gordo Kennedy, reconnected with Richards and was brought into the band to play keyboards. In fact, while demoing what would become their first, and only, album, the band shared a rehearsal space with the legendary D.O.A.

In June of 1980, the four piece went into Total Sounds West in Vancouver to record the album. Richards selected the studio because Cartlon Lee, who managed and engineered at the studio, was a famous West Indies recording engineer that had worked on Toots Hibberts’ biggest hits, and had also worked on the Rolling Stones Goat's Head Soup album.

With not much of a plan, the band booked two days to record material, unsure if they were going to get two songs done, an EP or something else. The session turned out to be remarkably fluid and in two days, the band recorded 12 songs, after which Richards overdubbed his vocals.

“I really thought about this album a lot before recording it,” Richards explains. “I had a definite concept of what I wanted to write about, how I wanted it to sound. I was a bit of a taskmaster. I laid down the law -- no beer! Just coffee and mineral water. We’re going to go in and bang it out!”

During mastering, the mastering engineer suggested that Richards go shop the record down in LA. In August 1980, Richards pressed the records through his own record label, called Hit Records. 1,000 copies of the LP were made along with 1,000 singles, the A-side being "Contaminated" and the B-side being “Do You Love It.”

Richards explains why he self-released the album. “At the time, people were releasing self-made albums. I liked that. Really simple, not the big corporate thing. Do the thing and get it out simply. At that time, I read that the Police put out an album for $5,000, I thought, “˜That’s’ the way to do it!’ I wanted it to sound good. I didn’t want it to sound cheap. The band had to be good and well rehearsed.”

“Everything was set to go, but then in September 1st of 1980, my wife left me,” Richards says. “I won’t go into all the melodrama, but I was devastated. Beyond devastated. Long story short, I dragged myself down to New York -- I had to get out of Vancouver. My sister was down in New York. In fact, at the time, she was subletting from Willem DeFoe, and was across the street from CBGB’s. She got married and moved and got a brand new phone number.” That’s the phone number that was on the back of my copy of the record!

“I went around to record companies and took the album in. I went to Atlantic Records. A lot of people liked the album. A guy at Island Records, who helped Madonna a year later, really liked the album. Another company said they really liked it, but no one would sign me,” Richards explains. “But, for some reason, no one would pick it up. “˜It’s a recession, blah, blah, blah.’”

“So, I went back to Vancouver, got served with divorce papers. Then, Gordon, our keyboardist, quit. So, we played one set as a three piece in a club. Then, the bass player and the drummer quit and I was all on my own again.” Richards put a new band together, including the guitarist from Troyka, and played one more club date. That’s the last time that the Flames music was ever played live.

“I had no band,” Richards continues. “Some people liked it, some people just didn’t get it. I got some heavy criticism from some circles, and then I got all tied up in this divorce. Then in ‘84 I moved to LA and tried to shop it and no one bought it there. It sort of then began the history of my life. And then, 34 years later, you called me up.”

You Always Survive

The Flames album is a record that circles numerous genres, but never quite settles in any of them. There’s the clean, pulsating synth lines of new wave. There’s the driving energy of power pop. And, perhaps, most strikingly, there are some lyrics that seem to hover between “fun” and truly dark.

Take a look at “You Always Survive.” It’s a song about getting beat up by the police, when suddenly, Richards states, “You always survive, no matter how bad it gets,” and then he sings the refrain in an almost Franki Valli doo-wop style. Then there’s “Stabbed To Death.” Able to go toe to toe with any Dead Boys or Misfits lyrics, it’s about getting stabbed to death. Then, there’s some sly sexual politics with “Menage a Trios,” which for 1980 was pretty edgy. Then there’s the cold ending, “Nothing Seems to Work Out.”

“I though about the lyrics as I was listening to it,” Richards says. “A lot of the lyrics on the album are what I was going through. Some are a little fictional. These days, when I write, I don’t write in a fictional manner. Then, I would get into a zone and would say, “˜Yeah, that’s cool, I would like to listen to it,’ even if it’s not true -- just so it affects me.”

“A lot has to do with the relationship I had with my wife at the time,” he continues. “It was strangely prophetic. Lo and behold, literally a week or two after finishing the record, she left me.”

But, despite having kicking riffs, despite lyrics that pushed contemporary boundaries, despite straight up rocking tunes, labels just wouldn’t sign the band. Perhaps because the album draws from so many sources, without falling in line with any of them, is what made it a difficult sell.

Richards muses, “My personal tendency is not to be part of any scene or any group. I tend to be a bit on my own. I didn’t consider myself new wave or punk. I didn’t care for labels. But, I was aware of what was going on. I like the idea of rock. I wanted a band to sound the way on stage the way the sound on record. I wasn’t really part of a scene.”

Richards continues, “Since we got in touch, I’ve been going back in time about a lot of things I haven’t thought about in years. I took this record down to a Vancouver paper for review. The reviewer write that it was “˜completely consumed with sex,’ and I was like “˜oh, man!’ I met with another person, who just said straight out that she hated the album! What could I do from there? I just Said, “˜Well, nice to meet you. Let’s just enjoy our coffee and that’s that.’”

“But, some people loved it. The CBS guy in Vancouver said that it was a “˜hot, little album.’ It was weird, though. There was this invisible shield where no one would sign me. I just wanted to get the album out there. I wasn’t asking for a whole lot of money. No one would make a commitment. I think in retrospect, there weren’t a lot of lyrics like this. Nowadays, it wouldn’t be such a big deal. Listening to it now, I’m really proud of it. f

With no one biting, with no band, and ties, Richards left Vancouver for LA “After that, I said that’s the last time I’m not going to be part of a band situation. I went and met up with Joey Levine in LA. He co-wrote “Yummy, Yummy” and some Plimsouls songs. We were best friends in LA. We wrote some stuff, and again nothing really happened. When I look at it from an objective point of view, I put out the energy, but nothing happened. Since the Flames, I’ve been writing constantly. I got to the point where I left LA in 1994 and I moved to New Mexico.”

“There was a long time where I was on my own. Music became my friend. I just like writing songs. I still write and record all the time. Eventually, I thought that you such just be able to play a song on a guitar and it should be viable. You don’t need a lot of production. Playing with an acoustic guitar is the truest way from my soul to the listener, because there’s no electronics. Somewhere, my obsession to “˜make it’ just dissolved and I just write music for the love of it. I just really like doing that. I haven’t put out any energy to put out anything in the business. I wouldn’t avoid it if the opportunity arose, but I’m not hankering for it. I have a great satisfaction from doing. I’ve probably written hundreds and hundreds of songs since the Flames..”

“And then, 34 years later, I get a call from you. This is really great. This kind of makes my life that someone out there that doesn’t know me, that is really into music, gets this album. I just really love that.”